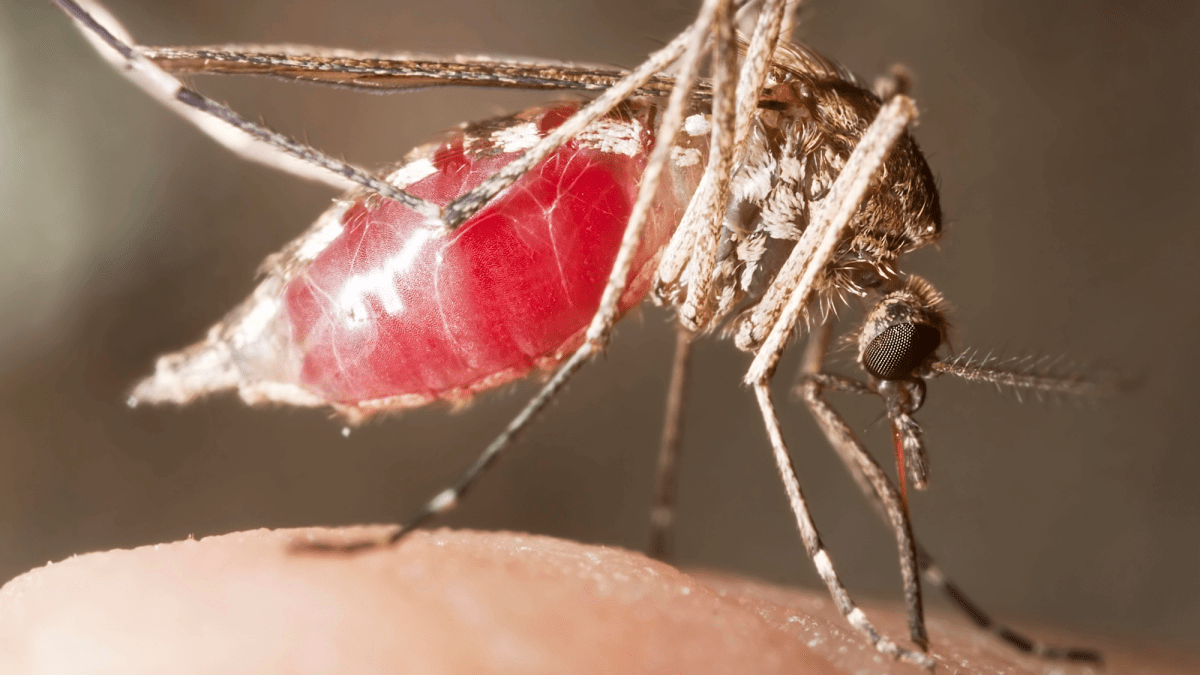

If you’re someone who mosquitoes just adore, we feel your pain. Unfortunately, new data indicates the number of mosquito species that feed on humans is increasing—and it’s likely to get worse.

Dr. Sérgio Lisboa Machado, a microbiologist from the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, is the co-author of a study published today in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution on a potential link between deforestation and mosquitoes’ increasing preference for human blood.

Whose blood is it anyway?

In the study, Machado and his colleague Dr. Jeronimo Alencar examined the feeding habits of several mosquito species in the Atlantic Forest, a moist broadleaf forest that stretches along the eastern coast of South America.

According to Machado, the project began as an attempt to figure out which local animals these mosquitoes were feeding on.

“When we started our research, our main goal was to find the preferred blood source that some species of female mosquitoes use for reproduction,” Machado tells Popular Science

The process of identifying the blood in the creatures’ stomachs was time-consuming. The first step was identifying which of the region’s roughly 40 mosquito species were biting. This involved careful scrutiny of the creatures with a stereoscope.

“The identification itself is not complicated,” Machado says, “but there is a shortage of entomologists to perform it.”

This fact, along with the need to transport the mosquitoes back to Rio de Janeiro for analysis, meant by the time the samples were analyzed, the DNA and RNA inside of them had started to break down. Even with these difficulties, the analysis provided Machado with a pretty good idea of which mammal species the mosquitoes in question preferred for dinner. In several cases, this blood was human.

“This was something we didn’t expect,” Machado says. “Since we were in a forest reserve, we expected to find DNA from vertebrates in the local fauna.”

Related Mosquito Stories

Shifting tastes

So why so much human blood? The researchers hypothesize that the Atlantic Forest’s changing environment has led these species to develop a taste for human blood.

“We believe it’s a matter of opportunity given the lack of a preferred food source,” Machado says. “It seems that if mosquitoes can’t find their preferred blood source, they seek out whatever is available.”

As biodiversity declines and animal species go extinct, more mosquito food sources are disappearing. However, unlike many of the animals on which they feed, mosquitoes are adaptable creatures. There’s almost always a ready-made alternative, including humans.

While this might be good news for the mosquitoes, it risks being terrible news for humans. As an increasing number of mosquito species develop a taste for humans, so too does the risk that species which have not been particularly problematic in the past could act as new vectors for blood-borne diseases.

Once mosquitoes acquire a new food source, they tend to develop a preference for that particular blood—and humans are one species whose availability is most definitely not declining. Today, the Atlantic Forest occupies barely a quarter third of its former area, and it’s not alone. With every passing year, more wilderness is lost to human incursion.

The answer seems to be first arresting, and then reversing, this process of deforestation and habitat destruction. But it’s not altogether clear that the damage is so easily reversible. Humans certainly aren’t going anywhere, so who’s to say that the mosquitoes won’t just keep feeding merrily on us regardless?

Machado expresses cautious optimism on how we can address how deforestation affects what mosquitoes eat.

“We believe this is a reversible process, but this will require restoring the biome while simultaneously continuing our study. We are still seeking more evidence that [these] mosquitoes have a preferred food source. For now, we are observing that there is a possibility that they are adapting to different sources and do not [prefer] human blood.”

Jumping species

Nevertheless, humanity continues to play with fire as it pushes further and further into previously unspoilt ecosystems. A landmark 2001 study found that new diseases are twice as likely to be zoonotic—transmissible between animals and humans—than existing ones. The danger posed by such diseases was exemplified by COVID-19, which jumped from bats to humans to catastrophic effect.

While disastrous scenarios surrounding a novel pathogen spread by mosquitoes are hypothetical, there are also very real dangers linked to deforestation. For instance, the malaria parasite in the Amazon is largely spread by the Anopheles darlingi mosquito. It was thought to have been eradicated in the 1960s, but re-emerged in the 1990s, and is now common. Another study found that cleared forest patches had created a perfect breeding environment for the insect, helping its return.

Ultimately, Machado stresses that it’s important to control the emergence of new disease vectors and thus mitigate further risks.

“The re-establishment of ecosystems will certainly contribute to this and should minimize the climate changes we are experiencing,” he says. “We need to learn that our actions today, however small, will always have global repercussions in the future.”

Environment,Animals,Biology,Climate Change,Diseases,Health,Insects,ScienceNews#forests #mosquitoes #turn #human #blood1768456014