In the 2023 movie Plane starring Gerard Butler, a commercial aircraft is caught in a terrible storm. Dark purple thunderclouds suffocate the sky. The plane shakes and the lights go out. Turbulence throws an unbelted passenger across the cabin. Eventually a lightning strike cuts the plane’s power, forcing it to crash land in a warzone, where the movie’s story really begins.

In reality, plane crashes in thunderstorms are extremely rare—largely because pilots seldom fly into thunderstorms in the first place.

“You’re never going to intentionally fly into a thunderstorm, because thunderstorms contain the roughest air, as well as other hazards,” says Patrick Smith, an airline captain and writer of the Ask the Pilot blog.

How pilots track thunderstorms

Avoiding thunderstorms, Smith explains, involves close collaboration between meteorologists, air traffic control, and the flight crew, both before and during the flight.

“We receive reports and forecasts before every flight indicating where storms might occur,” he says, referring to detailed satellite mapping provided by meteorologists. “But if you’re on a 12-hour flight, the information you have at the beginning is only so valuable. What you’re really relying on are the real-time tools.”

Part of the job of Smith and other pilots is to constantly monitor the plane’s onboard radar and Weather Avoidance System (WAS), which show “where storms are, how high they are, how fast they’re moving, the direction they’re moving and so on,” he says.

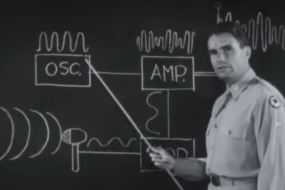

“[The radar] sends a signal out from the airplane and it bounces off the water in the clouds and comes back,” former pilot Tom Bunn explains. “The more water, the more intense the thunderstorm.”

Another key source of information comes from other pilots

“There might be 20, 30, 40 airplanes that [air traffic] control is watching at a certain altitude range,” Bunn says. “Everybody’s on the same frequency, you can hear each other. If you have turbulence, you’re supposed to announce it.”

This combination of radar and information-sharing allows pilots to track storms and rough air up to a couple of hundred miles ahead. They can then ask air traffic control for a change of altitude to avoid turbulence, or a change of route to bypass a storm. Most airlines recommend that pilots keep a minimum of 10 to 20 miles distance from thunderstorms, depending on their severity.

“You see with your radar, it’s color-coded,” Bunn says. “The green is the edge of the thunderstorm, that’s bumpy, but it’s not severe. The yellow would be pretty severe and then there’s red. You just want to stay out of that.”

Amazing Lighting show – How MASSIVE thunderstorms look on airliner radar scope!

Advanced weather radars in planes show pilots what parts of a storm to avoid. Video: Amazing Lighting show – How MASSIVE thunderstorms look on airliner radar scope!/ DIY with Michael Borders

How planes fly through storms

When flying through scattered thunderstorms, pilots may sometimes choose to chart a course through the gaps between the storms, rather than deviate too far from their planned path. In these conditions, the 20-mile distance guideline can provide an important buffer against unpredictable shifts in the weather.

“It can change very quickly and you can be in an area where a storm moves or morphs a certain way where that amount of clearance is impossible,” Smith says. “You won’t fly into the heart of the storm, but you may be skirting the edge of it from time to time.”

For the same reason, he says, it is usually not advised to fly over the top of storms—as the unfortunate pilot Brodie Torrance (Gerard Butler) attempts in the movie Plane.

“Thunderstorms can extend well into what we call the flight levels, upwards of 40 or even 50,000 feet,” he says. Although flying over the top of a thunderstorm can be smooth and safe, they can billow up quickly, making it safer to go around them than above them.

Related ‘Ask Us Anything’ Stories

Despite such strenuous efforts at avoidance, both Smith and Bunn agree that flying into a thunderstorm is rarely as perilous as the movies might suggest—although it could make for an uncomfortable ride.

“Probably the worst thing that can happen is you get hailstones, they make little tiny dents on the wing,” Bunn says. “If you dent the edge of the wing, it’s not going to be quite as efficient.” More severe hail can even crack the plane’s windscreen, although the vast majority of hail damage to airplanes is more a financial concern to the plane’s owner than a safety threat to passengers.

Thunderstorms are often also accompanied by heightened turbulence, which can be uncomfortable and frightening for passengers, but rarely unsafe. The pilot’s protocol is simply to set the autopilot to the optimum Turbulence Penetration Speed—calibrated to maintain stability while minimizing aerodynamic stresses—and ride out the bumps.

Why pilots avoid landing in storms

The one circumstance in which turbulence can be dangerous is when it occurs close to the ground, which is why pilots are particularly eager to avoid landing during thunderstorms.

“One of the big concerns is windshear,” Smith says. “Windshear is a sudden change in the speed and/or direction of the wind, which can be dangerous to planes at low altitudes.”

He explains that modern aircraft are equipped with windshear avoidance systems, and airports also have alerting systems for the phenomenon. If windshear is detected above the runway, “you may enter a holding pattern somewhere and wait for the weather to improve, or you may divert to an alternate airport.”

“Those decisions are made usually between the pilots and the dispatchers on the ground,” he says. “Ultimately, it’s the captain’s decision, but in practice it’s a collaborative thing.”

And what about the greatest fear of many nervous flyers, a direct lightning strike like the one that takes out the aircraft’s power systems in Plane?

Lightning hits plane leaving BC airport ✈️⚡️ #LightningStrike

Planes are designed to withstand lightning strikes. Video: Lightning hits plane leaving BC airport/ @globalnews

“It’s not a problem,” Bunn says. “The average plane gets hit, I’m told, twice a year.” The electrical systems of commercial aircraft are designed to withstand these shocks, with backup systems that take over in the rare event of failure.

“It’s like if lightning hits your car, it just follows the skin,” he explains. “Doesn’t do anything to people inside the car. Same with the airplane. If you get hit by lightning, you just have a flash and a loud noise.”

In Ask Us Anything, Popular Science answers your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the everyday things you’ve always wondered to the bizarre things you never thought to ask. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.

Science,Ask Us Anything,Aviation,Environment,Technology,Weatherevergreen,Features,News#pilots #avoid #thunderstormsand1768228351