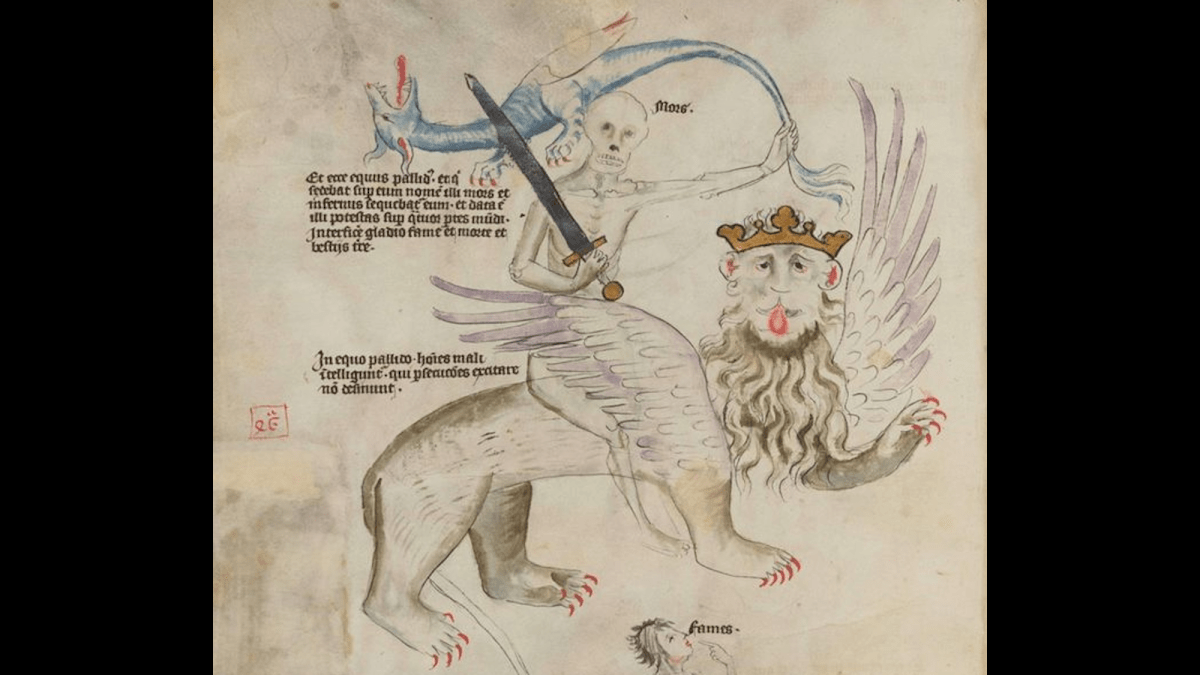

The Black Death (Yersinia pestis) killed as much as half of Europe’s total population between 1346 and 1353, so there are a lot of bodies buried across the continent. For example, contemporary accounts from Thuringia—a state in central Germany—report that about 12,000 plague victims died around Erfurt amid the city’s outbreak in 1350. But despite multiple accounts attesting to this devastation, none of the 11 mass graves could be pinpointed for centuries.

Now, an archaeological team including researchers from Leipzig University believe they have finally located one of those infamous burial sites. According to their study recently published in the journal PLOS One, land near the deserted medieval village of Neuses contains clear evidence of human remains, as well as the hastily mixed soil that covered the bodies.

“Our results strongly suggest that we have pinpointed one of the plague mass graves described in the Erfurt chronicles,” explained study co-author and Leipzig University geographer Michael Hein.

The suspected burial plot is fascinating not only for what it contains, but how it was identified. Instead of accidentally discovering archaeological evidence amid a construction project (as is often the case), Hein and colleagues used interdisciplinary techniques to seek out the potential Black Death burials. To do this, the team analyzed the ground beneath them using a process called electrical resistivity mapping. Every type of geologic material possesses some degree of electrical conductivity, which can be charted by firing currents into the earth and measuring resultant voltages. This allows researchers to correlate voltage to various soil and rock types.

At one location, Hein’s team identified a roughly 33 by 49 by 11.5 foot site with noticeably disturbed subsurface sediment distributions. Subsequent drilled core samples produced mixed geologic materials along with the fragments of human remains. Additional radiocarbon dating indicated the remnants dated back to the 14th century. Taken altogether, it strongly suggests a medieval mass grave.

Apart from the bodies, the sediment composition itself supports the Black Death burial theory. The village of Neuses was likely settled in part due to its fertile soils known as chernozems. However, the grave pit is located in a drier region near a valley edge of the Gera River. It stands to reason that instead of interring Black Death victims in wetter soils closer to the town, the residents of Neuses opted to place them in drier conditions far outside the village walls.

“This finding aligns with both modern soil science and the medieval ‘miasma theory,’ which held that diseases spread through ‘bad air’ and ‘vapours’ arising from decaying organic matter,” said study co-author Martin Bauch of the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe.

The team’s hypothesis won’t be confirmed without an actual excavation at the site, but until then, their novel approach paves the way for additional searches. This technique isn’t relegated to plagues of the distant past, however. Hein, Bauch, and their collaborators believe similar approaches can be applied to various other archaeological searches.

Science,Archaeology,Diseases,Health,Technologyculture,geology,history,News#Medieval #plague #victims #mass #grave #Germany1768338265